A review of literature on the progression of spondylolisthesis—a common diagnosis in older adults suffering from back pain—explores the ailment’s predictive stages and radiographic features associated with each stage in the hope of establishing a reliable clinical timeline in which each phase of the condition presents itself.

Epidemiology

When an anatomical displacement of the anterior or posterior vertebra disrupts the stability of the spine, the structure of the vertebral body or arch may be compromised. The condition—whether dysplastic, pathogenic, or traumatic—sets into motion a chronic degenerative process that affects the surrounding protective connective tissue. Degenerative spondylolisthesis most commonly occurs in older adults (50 years plus) and is up to six times more likely in females than in males. However, because it may also be found in six to roughly 20 percent of the general population, genetic or environmental factors may also play a role in its development.

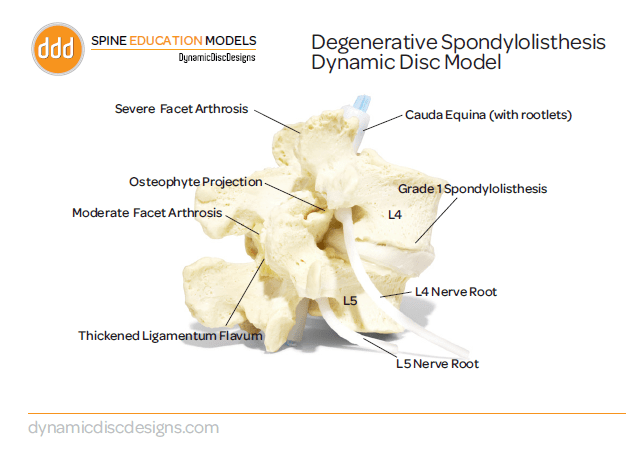

The lower lumbar vertebrae bear the greatest loads, making them the most vulnerable to degeneration. The cervical and (rarely) thoracic area may also develop spondylolisthesis when the costal architecture surrounding these regions attempts to stabilize. Most commonly, spondylolisthesis occurs at the single level of the L4-L5 vertebrae, with a low incidence of occurrence at L5-S1 and L3-L4 anterior displacement, often in concurrence with L4-L5. The rate of displacement is commonly graded between one-to- five, based on how far the vertebral body has slipped past the subjacent vertebrae, as noted in intervals of 25 percent. Spondylolisthesis is diagnosed at grade five, when the entire vertebral body has slipped beyond the edge of the subjacent vertebrae.

Different Theories

Typically, high-grade anterior displacement beyond 30 percent does not occur with degenerative spondylolisthesis, and there appears to be little correlation between the progress of degeneration and the degree of pain in patients. While the method of identifying the degree of vertebral deviation is historically valid and effective, it does not take into consideration other common radiographic features, and the condition’s pathophysiology has remained a controversial subject. Some scholars attribute spondylolisthesis to spinal instability stemming from intervertebral disc changes. Others believe that age-related or other changes in the facet joints create a dynamic that eventually leads to vertebral slippage. While this idea is unrefuted, controversy over how much instability and eventual slippage are caused by facet joint degeneration persists, with some attributing the instability to arthritic changes and others emphasizing other contributing factors, such as ligament laxity due to hormonal or other changes. In any case, segmental instability occurs over time due to disc and facet degeneration, and the associated anterior/posterior ligaments and ligamentum flavum mechanical strain eventually leads to displacement.

Common radiographic markers of lumbar segmental instability include dynamic translation of greater than 3mm on flexion-extension or sagital rotation of greater than 10 percent. The condition, however, may be difficult to detect on supine MRI images, as increased facet joint and ligament laxity allows for a dynamic in which weight-bearing vertebrae may be held in temporary suspension and revert to its proper physiologic position during supine scans. Therefore, it is advisable to compare a neutral standing scan to a supine MRI, rather than a flexion-extension radiograph, when looking for evidence of dynamic instability.

Roughly one-third of patients may experience a further progression of their lumbar slippage, though even in those suffering from grade one or two spondylolisthesis without fusion who have undergone minimally invasive decompression surgery, the rate of slippage beyond five percent is seen in only 32 percent within two years of the procedure. The motion-limiting nature of intervertebral disc segments protects against degenerative progression, and any severe reduction of joint and disc space will lead, over time, to an auto-fusion of the vertebrae at the facets and endplates, as seen in end-stage spondylolisthesis.

Radiographic Features Identifying Three Stages of Spondylolisthesis

The three stages of spondylolisthesis—degeneration, instability, and restabilization—are recognizable via six visible radiographic features—facet morphology/arthropathy, facet effusion, facet vacuum, synovial cyst, interspinous ligament bursitis, and vacuum disc. These features provide a reliable timeline of the disease progression.

Conclusion

The process of spondylolisthesis begins with degeneration of intervertebral discs or facet joints and progresses through instability and restabilization. It may be initially marked by the presence of a facet vacuum. Fluid eventually accumulates within the facet joint space as the vertebral segment progresses through various stages of mobility. This effusion may be considered a reliable early indicator of instability, followed by (with further degeneration) facet arthropathy, degenerative disc disease, and posterior ligamentous complex pathology, including cyst(s) and bursitis. In advanced facet osteoarthritis, the effusion may be replaced by a vacuum, which may cause cleft formation and further degeneration. Eventually, an autofusion of the vertebral facets and endplates may be observed. While the review provides insight into a complex phenomenon, it emphasizes that individual patients may present the progression of degenerative spondylolisthesis uniquely and should always be treated and diagnosed with a personalized approach.

Share Now